TMITBD

Act One:

Deep FragmentsKelvin Vu

This is a map, as it travels across space. But it is also a story, as it traverses time. We start at the beginning and conclude at the end, so where else could we begin other than the cosmos?

The first theory of uranium's material origins posits that it forms when a star runs out of energy, collapses in on itself, and produces a supernova explosion. 1

A more recent theory states that the immense gravity of two neutron stars causes a cataclysmic collision that produces and then jettisons heavy elements into space. 2

By either or both theories, uranium then gets swept into the gravitational formation of Earth.

In name, uranium comes from Uranus, god of the heavens and sky, who the Ancient Greeks imagined arched over his mother and lover, Gaia, the Earth.

Uranus falls from power when he tries to bury his children deep within Gaia, only to be overthrown and castrated by his youngest son, Cronus. 3

In 1781, composer William Herschel deduces that a cosmic body moving through the constellations is not a star but a planet. Astronomers name it Uranus, after the god.

Martin Klaproth then names his newly discovered element uranium, after Uranus the planet.

In 1896, Henri Becquerel discovers that uranium emits invisible rays by observing the shadows they cast on photographic plates. 4, 5

This finding lays the foundation for the Atomic Age fifty years later.

The oldest known examples of art are hand stencils on the walls of Spain's Maltravieso Cave. Archaeologists measure uranium's decay into thorium in the wall's minerals, and determine the prints to be those of Neanderthals from more than 64,000 years ago, before the first modern humans migrated to Europe. 6

In Pliny the Elder's Natural History, Corinthian maid Dibutades mourns her lover's imminent departure, uses lamplight to cast his shadow onto the wall, and traces his profile to preserve his silhouette after he leaves.

A cave and then a wall becomes a screen for the transmission of loss and desire through the scenography of projection. 7

On August 6, 1945, the United States detonates nuclear bomb Little Boy over Hiroshima.

Its destructive repertoire includes the flash burn effect that leaves visible shadows of people's bodies on sidewalks and roads when the blast kills them on the spot. 8

One shadow at the entrance of the Sumitomo Bank records where a person had been sitting waiting for the bank to open. Conservators at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum are now trying to preserve the shadow's integrity. 9, 10

What affects and desires does this scenography transmit?

Ionizing radiation is imperceptible, but brought into presence by its effects.

Acute exposure can burn and cause the rapid and lethal breakdown of the body's systems. 11, 12, 13

Uranium itself is not as dangerous as its decay daughters that continue to release ionizing radiation until the end of their decay chains. The half lives of such radionuclides can range from seconds to billions of years, collapsing instants and eternities at the atomic level.

The health effects of low-dose exposure may not appear for years or even decades and be hard to detect among the myriad factors, including random chance, that produce mutations, both hidden and noticeable.

Radiation can fundamentally alter DNA in ways we may or may never notice, a form of embodied witnessing beyond cognition.

Is this what fears us most? That, like Uranus, we may produce forms we no longer recognize and can't control.

DECAY CHAINS / MUTATIONS 3

Who decides what is deformed and what is novel?

When is a daisy no longer a normal daisy? 14

Congress selects the salt beds near Carlsbad, New Mexico, in 1979 and Nevada's Yucca Mountain in 1987 to permanently store radioactive waste deep underground.

Both sites promise geologic stability and containment from the elements.

But how do you keep people from unearthing the dangerous materials over the far time horizons of their decay?

Ten thousand years is more than twice the age of the oldest known language spoken today. 15, 16

Familiar constellations will have shifted by 50,000.

And scientists estimate that the buried waste may still be dangerous for 300,000 years, as long as the entire duration of the human race.

The Human Interference Task Force and Futures Panel turn to the visceral and emotional when we can’t rely on the durability of shared language and physical structures.

In 1999, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant starts accepting nuclear weapons waste.

But the Yucca Mountain Project stalls, leaving no permanent repository for the 90,000 metric tons of radioactive materials temporarily stored in pools and dry casks across the country.

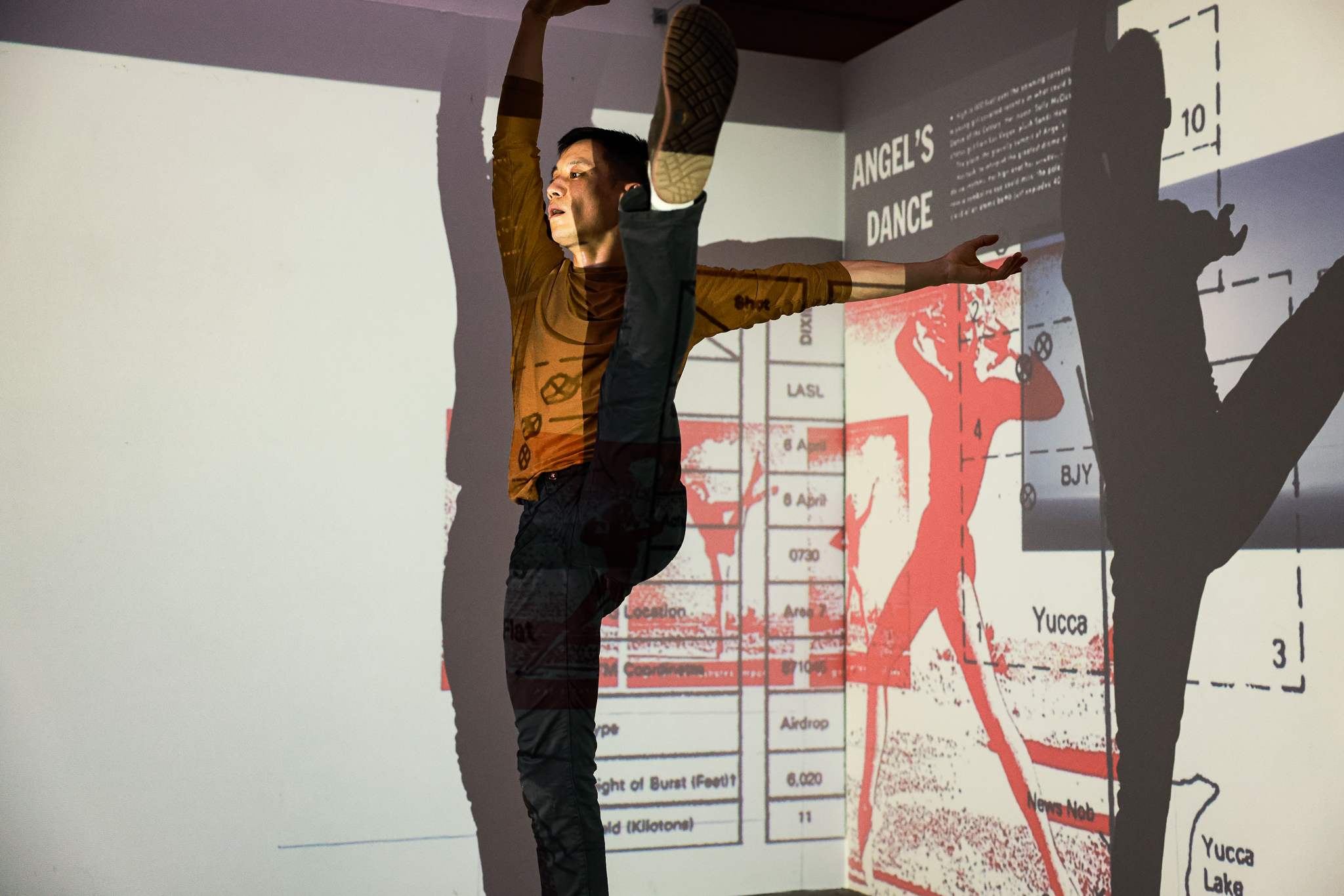

On the Yucca Flats on April 6, 1953, an 11-kiloton nuclear bomb explodes at dawn, the fourth detonation of Operation Upshot-Knothole. At 6,000 feet above the ground, the DIXIE test explosion is too high to pull desert debris into a vertical column and creates a mushroom cap with no stem.

Forty miles south on Angel's Peak, Las Vegas ballerina Sally McCloskey interprets the drama in four poses: 17

Apprehension starts the dance.

Two illustrates Impact.

Three is a symbol of awe.

Four is the climax, a brisk pose of survival.

Apprehension.

Impact.

Awe.

Survival…

In John Gast’s 1872 painting, American Progress, Columbia glides westward into the future, bearing the “Star of Empire” and summoning the light of the sky to dispel storm clouds before her. In her right hand, she holds a school book, while her left strings telegraph lines across the landscape. The drape of her dress trails behind her like wings.

Native Americans and wildlife flee into the dark of the West, with farmers, settlers, covered wagons, and trains in relentless pursuit. 18

…Apprehension.

Impact.

Awe.

Survival.

ANGELS 3

In contrast to Columbia’s soft assuredness, Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus is tense and torqued with opposition, wings forced open, propelled by the storm of progress with wreckage at his feet. 19, 20

In material and in the imagination, we are caught between facing front but looking back, between hurtling forward and stopping to survey the damage.

…Apprehension.

Impact.

Awe.

Survival.

The major fault that runs through Yucca Mountain gets its name from the local origins of the Ghost Dance, a Native American practice that promises to bring the Messiah, resurrect dead ancestors, and return the land to pre-colonial abundance. 21

But settlers' fear of the dance as militant leads to the Wounded Knee Massacre and a government ban on the practice. 22

By Kelvin Vu

TMITBD is a landscape choreographic performance about Three Mile Island (TMI) near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The piece combines movement, sound, and animation to explore meaning making in the face of crisis, archival gaps, and the simultaneity of too much and too little information.

Three Mile Island housed two nuclear reactors and was the site of the worst commercial nuclear accident in US history. In its 1980 report to Congress, the US General Accounting Office referred to the 1979 partial meltdown at TMI as the “most studied nuclear accident in history.” But there are still ongoing questions about the health and ecological effects of the radiation releases.

TMITBD explores official and unofficial narratives, evidence collection, and bodily witnessing of landscape change. By speculating on how performance can make choreographic and landscape dynamics sensible, it also proposes avenues of practice for landscape architects as researchers, designers, performers, and bodies.

TMITBD began as my thesis project in the Landscape Architecture Department at the University of Pennsylvania, Weitzman School of Design. Special thanks to my advisors, Robert Gerard Pietrusko and Catherine Seavitt.

DOCUMENTARY CHOREOGRAPHY

COMING SOON

2 Projectors

35 Minutes

Link to the full performance

Performance Recording byRudy Gerson

Performance Photography by Chaowu Li