Incantational Contaminations

Part One: Demon Bowl EcologyMiriam Saperstein

“And in three ways [demons] are like humans: They eat and drink like humans; they are fruitful and multiply like humans; and they die like humans.” —Chagigah 16a, Babylonian Talmud (author’s translation)

The demon, now dead, must have feasted before coming here. Charged up with stolen life force, the fecund creature was drawn to an egg placed under an upside down bowl, shallowly buried in the yard.

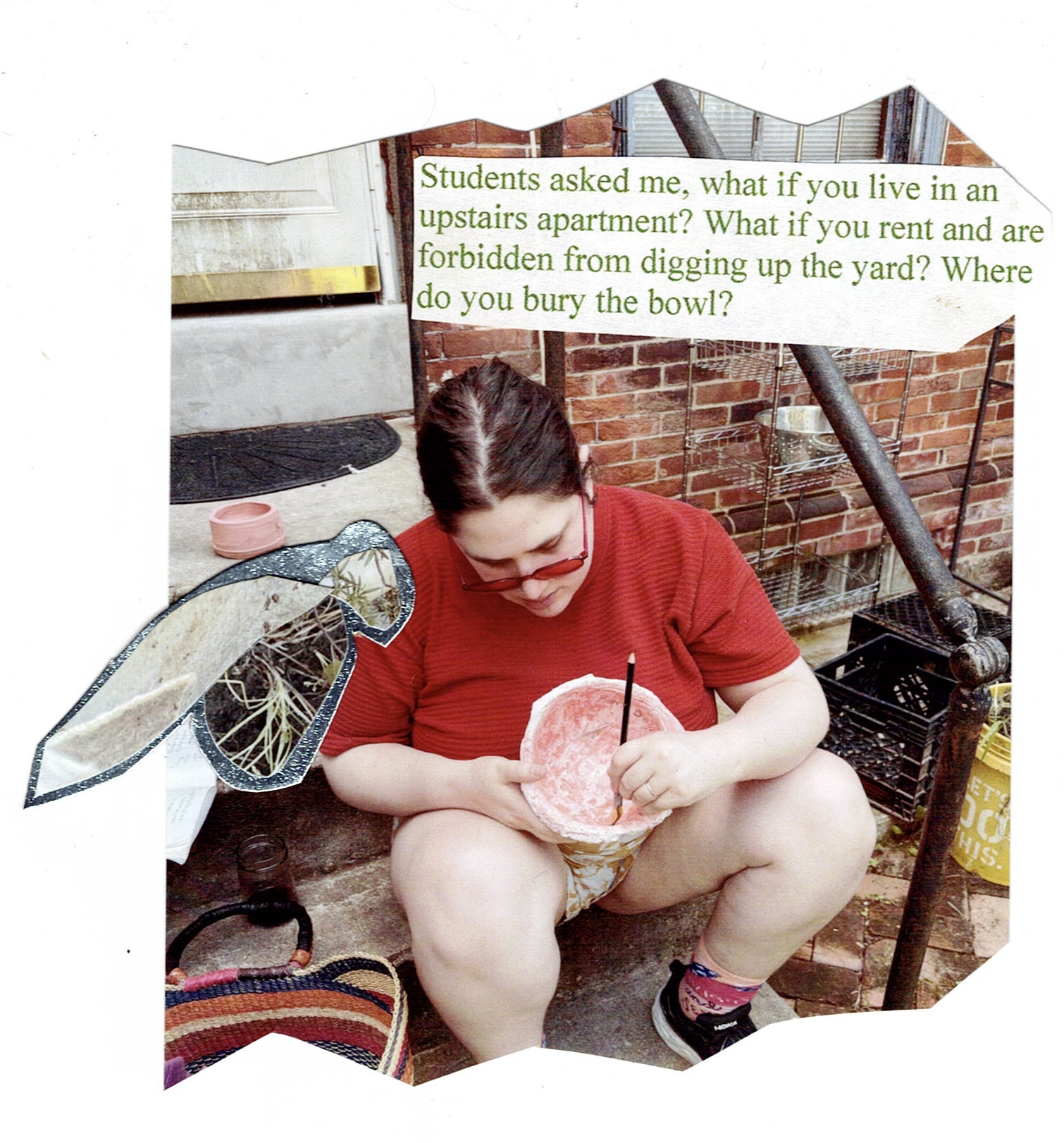

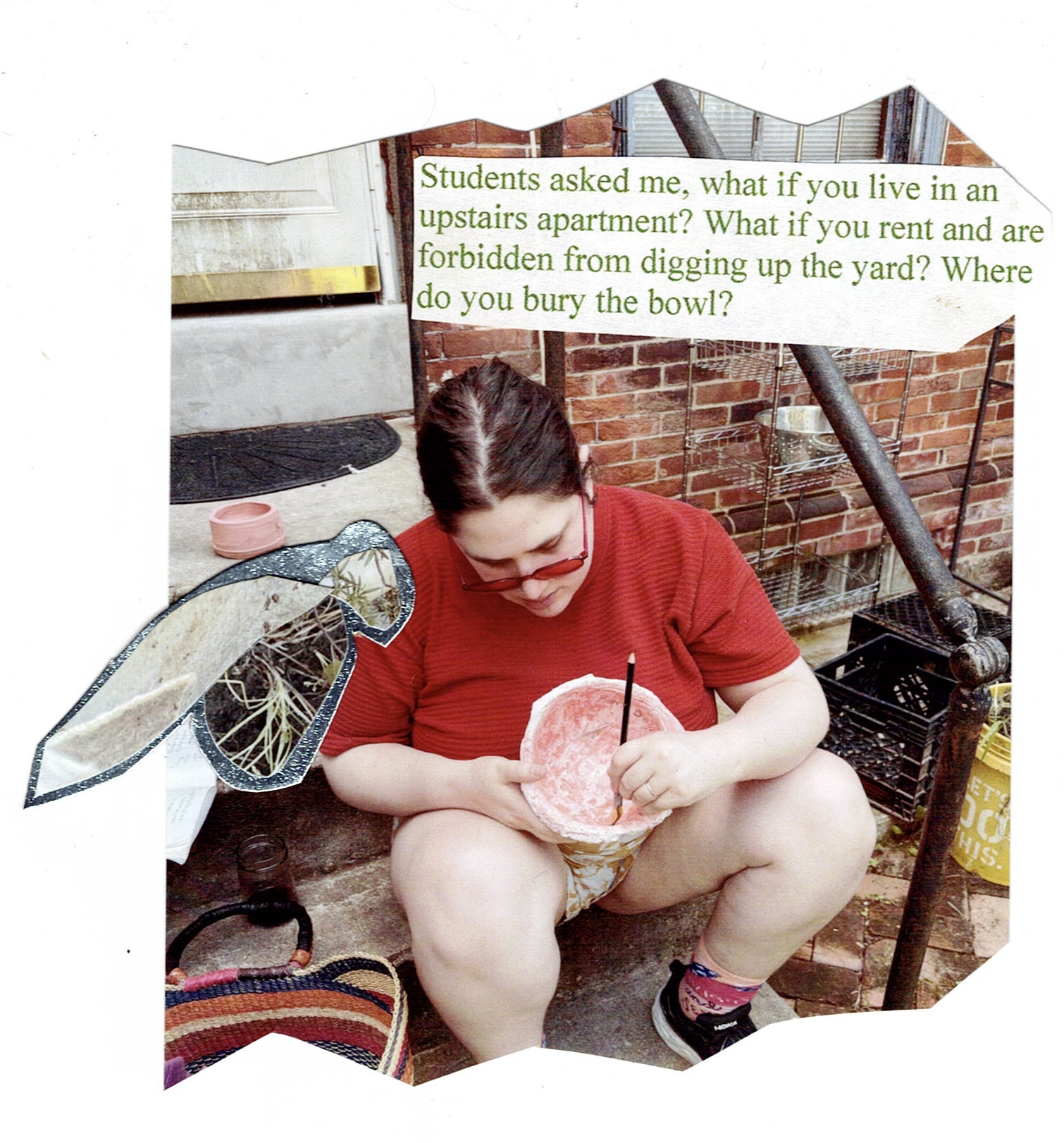

A human buried the bowl. That was me. Typically, such a bowl would have been buried in the corners or threshold of a late-ancient Babylonian home. Western academics have since dubbed these amulets demon bowls, or Aramaic incantation bowls. This protective technology was developed and widely implemented throughout the Babylonian empire from around the fifth to seventh centuries CE. A person would commission a scribe to make this object. The scribe would take a ceramic bowl and ink an Aramaic or asemic inscription on the concave side. These inscriptions invoke a range of religious powers (gods, Jesus, rabbis, etc) and are sometimes accompanied by images of bound demons. Demons trying to enter the home would instead be drawn to the bowl at the boundary and get trapped inside.

I couldn’t dig a hole directly by the front door, as is the custom– the steps leading up to the threshold are concrete. I tried to dig a hole beside the steps, but hit either clay or pipes. My shovel is adequately cared for, but I didn’t want to risk it. I rubbed more sunscreen into my cheeks and stepped further from the house. At the base of the fig, I tried again, dislodging clumped daffodil bulbs. I did not plant this yard but the placement of since-overcrowded perennials shows intention. I dug about six inches deep, put the egg in the hole, and covered the egg with the bowl, backfilling with dirt. I worried the egg would smell. I worried this wouldn’t work, or that the bowl would lead demons to my house like a beacon, then fail to adequately trap them. I looked at the soil, deciding whether to pray. I just said, “please work,” and went back inside, locking the door.

The bowl is inscribed with an incantation. This web of intention catches the demon as it reaches for the egg, keeping it from burrowing. Consider the rain, the smell of the demon inside. How does the ambient static shift when the demon realizes they can’t leave their bowl?

The demon does not escape, and dies, leaving the demon’s gut in pregnant pause, brimming with viruses, spores, baby demons. Do they hatch, or birth live young? Who midwives the demon births? Can only Demon Mommy Lilith give birth, queen bee? What are the names of Lilith’s demon midwives? Who screams when Lilith gives birth?

It’s getting stinky in here, this anaerobic chamber. Apoptosis—tiny death of every demon cell that eats itself from the inside out. Some cells die sooner than others, a spectrum death. Gut bacteria fester, skin bubbles. The form, if body, bloats, doming, then deflates, leaking. The only escape is fluid or in parts.

This is in the case of a demon bowl buried in a muggy American city, in leaden dirt. In hotter, drier climates, the demon would mummify. In the case of two bowls glued together with pitch, the pre-death demon would pace, spinning the ball around and around, tilling the sand. Even if sealed, sealed dry. Even once dead, the demon’s restless ghost would run towards the wall, turning the dry trap.

The metaphysics of a ceramic bowl, however sealed, wherever buried, always suggests a one-way permeability. A Hotel California effect, wherein a demon enters from outside-in and cannot escape, neither as living form nor ghostly after-presence. This metaphysical limit seems unique to demon-kind, because where a bowl was buried shallowly in topsoil, the mites and mealworms and other scavengers burrow in. Now they feast, eating chunks of demon flesh, skin, dust. They use the demon hair to nest, the demon eyelashes for minute domestic weavings. Fungal networks reach in, rhizomatically mapping the vein-ways, feeding in preparation to fruit. In this microclimate below the bowl’s dome, the hungers of biologic life tangle with soil’s tendencies, forming a web with demon urges, bound by the incantatory imperatives that spiral overhead.

The networks feed in order to fruit, and fruit they do, implying that the mushrooms at least can reach beyond the ceramic barrier. An observer of such a world has a choice—what forms the edge of each body? What is the one-way impermeable membrane that makes a worm a worm, and the nitrous glob it eats no longer decayed root of a plant-self, but cellular structure and sustenance of worm-self? To map the boundary of a self makes possible the mapping of how one self acts on another, not as inseparable parts of a whole, but as unique structures of agencies, ones that can be narrativized as competition, care, strategic compromise. This creation of agent has also been used to define a subject, a self without agency that is merely acted upon. Power extracted and fed on by a greater entity. Whose selfhood is prioritized when the beings each become separate?

The late ancient rabbis lived within the Roman and Babylonian empires, in which they were subjects with limited agencies determined by freedom-status, gender-state, age, and control of land. Rather than map the self to exert full power of agency, these rabbis mapped their worlds through obligation. Obligation was the web that held it all together—a human must act in service of a G!d who must create the world, because that is what a lonely G!d does. Reproduction, digestion. Men and their wives governed by the times. Who is obligated by the turning of the sun to bless. Freedom meant obligation to each other and to G!d, and thus the ones who wanted to be in power created extensive taxonomies to determine the extent of each self’s obligations. These lists populate the Talmud, their canon, with a shifting mobile of selves. They dazzle, moving and overlapping in the light. A demon is like an angel in three ways. Another three ways animal. The comprehensive lists, scales, and measures seem to span the whole of creation, beyond even what the eye can see, reaching what the internal constellation of what a body knows— the eyes of an angel raising the hairs at the back of the neck, the tongue of a demon tugging at the veins. The rabbis said humans are like demons in only three ways: we eat and digest, we are birthed against our wills, and we die, often alone but surrounded.

Birth and digestion seem to require that a demon essence must also have a material element (in this level of reality, or maybe only in some materially analogous realm, the layer that is pushed up against this one). The material corpus, limbs and matter forming the demon-self’s body. The demon form, even a demon body, still might not be visible to human eyes. In the beis midrash, why are the shoulders of the students’ jackets smudged and worn even though they have but bent their heads in study all hours of the day? The rabbis say, the demons are drawn to this place of vitality. The Torah they study is the tree of life. Demons, too, flock to the study hall. In this packed space, the demons jostle the shoulders of the students to feed on the flowing life force of Torah.

And in death, what changes? What remains remain? The rabbis maintain that a demon, like a human, digests. If it can digest, it can be digested. Humans would only see a dark ring of moist soil, wet from demon leaking. Bugs crawling around, tugging at pieces. But the bugs can see the demon body, a shimmery husk. Like a wasp’s nest—dried pulp, an array of holes and strings.

When I read about human rabbis trapping demons, wives unbound from set prayer times by their gender, the rites of tending to a dead relative’s body, that is to say—when I study the Talmud, or the incantations written on the demon bowls and other protective amulets, I get caught up in determining goodness, as if that is the true measure of whether a life cycle moment should occur. Goodness, like naturalness, is the domain of the human men, who must protect their livers from demonic meddling, their wives’ dreams from infiltrating. Like the rabbis who curse Lilith for spilling their seed as they turn desirous in sleep, I want to know who’s to blame. Am I sick because of demons in my blood? Am I sick because, I settler, live in a paradigm in which my presence infiltrates indigenous homeland? I arrive not by crossing a welcoming threshold, but through force and genocidal policies, tangled up in human migration. How much am I part of the Empire at hand? Am I more demon or human? Is that a question of goodness or of whether I have agency to choose a variety of actions? For the rabbinic taxonomy that hinges on obligation is based on an understanding that demons and angels act on the world in one direction, unable to choose their one type of action. A demon is a tube towards the most material, separated realm of distinctions. An angel is a tube towards the most undifferentiated realm of oneness. In human-land, our realm in the middle, humans interact with a range of motions to the set and singular motions of angels and demons. Demons feed on and separate the body from itself, the home from its wholeness, a family from its status of complete security. They are drawn to life force in order to take that oneness and make it into distinct, consumable parts. If demons are as physically consequential as the ancient amulets suggest, should I keep trying to trap them? Will I actually be safer this way? If humans are somewhat like demons, as rabbinic taxonomies suggest, and since I’m not of the belief that we should trap and kill humans, or “demonize” humans carcerally, it’s hard for me to believe that demons are inherently evil or must be eradicated. To take a material stance, I must look to the larger web of life, and act in service of the continued hold of that web on the reality I live in. In other words, the webs of Empire and coercive control are just as tangled up in the material of this world as the living sky, the stones, the stories that we pass from generation to generation. And any action tugs at that web, reinforcing parts or straining others.

If settlers can be demons, infiltrating homes, then I can be a settler, burying this bowl. This version of reality would not be salient to the rabbis who mapped these taxonomies. The rabbis lived within Babylonian and Roman rule. When is taxonomy a danger to Empire? When a danger to the victims of State? When is taxonomy inherently violent and useful? Rather than taxonomic purity—What is the whole? Where does a cycle of self begin? What consciousness is activated? How porous?

They are hungry. Anything is possible. These bacteria could eat the whole world. They’ve been yearning. They act quickly, popping the bubblers, devouring what’s in their path. They eat each other, get too full, and die. They have been waiting for this.

The soil rests comfy. Within them a well-established fine web of mycelia, nettle roots, daffodil bulb, insects and worms. Polyphonic breathing—the exchange and rhythm. A sharp jag—somewhere along the pathways, a rupture. Sudden sting of acid on tender root tips. Flood of nitrous bile.

When a holy life becomes a death, ghosts reverberate from life. Ancient amulet users, so afraid of demons drinking domestic blood, of reverberations within the domestic sphere. Boomerang effects. A return to scientific empiricism, which is to say, Western eugenics. Are ghosts just whatever smudges on human thoughts or the actual life force of the demon? What do the ghosts want? Maybe demons don’t have ghosts–in life, they seek out life, and in death they seek out a way to fall apart, to give that life force back into decay, eventual rebirth, re-watering soil. Precipitation of ideology in which everything non-human is pure and simple. I don’t believe we are the only life forms that have muddy emotional relationships to ethics.

A small beetle senses a ripple when the body pops from the pressure, a subsequent soft deflation in the soil tension. They make their way over, routing around worms squirming through tunnels made by the reaching of roots, mycelium's grasp. Water tapping, trickling over ceramic, the hardened form buried in its own beginning, a slow maintenance of wet pressure, until this beetle, too, is damp. In the surrounding clay-heavy soil, they taste medicine, a wash of iron.

As the nettle roots over-feed on nitrogen, their skin blisters, shrivels, cell structure caving, the once-taut stalk collapses. They are disintegrating into their constituent parts.

Amidst demon-fall, a biome flourishes! A mite peers around at shiny. They covet the internal structure, want to make this a home. They are well-fed in this depth, but their belly aches for more. Will there be enough in time? They listen for the hiss of bigger bugs.

A long-nosed pincer smells the proteins in the egg yolk and burrows towards it, ready. They pierce the shell and the white goo beads up at the puncture. They suck it out with a long proboscis, tiny flakes of egg shell in their hairs, then scuttle away so as not to become someone else’s lunch. There’s a pressure here, above the egg. Something tangled and potent, but none of the bugs are going to fuck around with that. It’s not for them.

The demon does not escape, and dies, leaving the demon’s gut in pregnant pause, brimming with viruses, spores, baby demons. Do they hatch, or birth live young? Who midwives the demon births? Can only Demon Mommy Lilith give birth, queen bee? What are the names of Lilith’s demon midwives? Who screams when Lilith gives birth?

It’s getting stinky in here, this anaerobic chamber. Apoptosis—tiny death of every demon cell that eats itself from the inside out. Some cells die sooner than others, a spectrum death. Gut bacteria fester, skin bubbles. The form, if body, bloats, doming, then deflates, leaking. The only escape is fluid or in parts.

This is in the case of a demon bowl buried in a muggy American city, in leaden dirt. In hotter, drier climates, the demon would mummify. In the case of two bowls glued together with pitch, the pre-death demon would pace, spinning the ball around and around, tilling the sand. Even if sealed, sealed dry. Even once dead, the demon’s restless ghost would run towards the wall, turning the dry trap.

The metaphysics of a ceramic bowl, however sealed, wherever buried, always suggests a one-way permeability. A Hotel California effect, wherein a demon enters from outside-in and cannot escape, neither as living form nor ghostly after-presence. This metaphysical limit seems unique to demon-kind, because where a bowl was buried shallowly in topsoil, the mites and mealworms and other scavengers burrow in. Now they feast, eating chunks of demon flesh, skin, dust. They use the demon hair to nest, the demon eyelashes for minute domestic weavings. Fungal networks reach in, rhizomatically mapping the vein-ways, feeding in preparation to fruit. In this microclimate below the bowl’s dome, the hungers of biologic life tangle with soil’s tendencies, forming a web with demon urges, bound by the incantatory imperatives that spiral overhead.

The networks feed in order to fruit, and fruit they do, implying that the mushrooms at least can reach beyond the ceramic barrier. An observer of such a world has a choice—what forms the edge of each body? What is the one-way impermeable membrane that makes a worm a worm, and the nitrous glob it eats no longer decayed root of a plant-self, but cellular structure and sustenance of worm-self? To map the boundary of a self makes possible the mapping of how one self acts on another, not as inseparable parts of a whole, but as unique structures of agencies, ones that can be narrativized as competition, care, strategic compromise. This creation of agent has also been used to define a subject, a self without agency that is merely acted upon. Power extracted and fed on by a greater entity. Whose selfhood is prioritized when the beings each become separate?

The late ancient rabbis lived within the Roman and Babylonian empires, in which they were subjects with limited agencies determined by freedom-status, gender-state, age, and control of land. Rather than map the self to exert full power of agency, these rabbis mapped their worlds through obligation. Obligation was the web that held it all together—a human must act in service of a G!d who must create the world, because that is what a lonely G!d does. Reproduction, digestion. Men and their wives governed by the times. Who is obligated by the turning of the sun to bless. Freedom meant obligation to each other and to G!d, and thus the ones who wanted to be in power created extensive taxonomies to determine the extent of each self’s obligations. These lists populate the Talmud, their canon, with a shifting mobile of selves. They dazzle, moving and overlapping in the light. A demon is like an angel in three ways. Another three ways animal. The comprehensive lists, scales, and measures seem to span the whole of creation, beyond even what the eye can see, reaching what the internal constellation of what a body knows— the eyes of an angel raising the hairs at the back of the neck, the tongue of a demon tugging at the veins. The rabbis said humans are like demons in only three ways: we eat and digest, we are birthed against our wills, and we die, often alone but surrounded.

Birth and digestion seem to require that a demon essence must also have a material element (in this level of reality, or maybe only in some materially analogous realm, the layer that is pushed up against this one). The material corpus, limbs and matter forming the demon-self’s body. The demon form, even a demon body, still might not be visible to human eyes. In the beis midrash, why are the shoulders of the students’ jackets smudged and worn even though they have but bent their heads in study all hours of the day? The rabbis say, the demons are drawn to this place of vitality. The Torah they study is the tree of life. Demons, too, flock to the study hall. In this packed space, the demons jostle the shoulders of the students to feed on the flowing life force of Torah.

And in death, what changes? What remains remain? The rabbis maintain that a demon, like a human, digests. If it can digest, it can be digested. Humans would only see a dark ring of moist soil, wet from demon leaking. Bugs crawling around, tugging at pieces. But the bugs can see the demon body, a shimmery husk. Like a wasp’s nest—dried pulp, an array of holes and strings.

When I read about human rabbis trapping demons, wives unbound from set prayer times by their gender, the rites of tending to a dead relative’s body, that is to say—when I study the Talmud, or the incantations written on the demon bowls and other protective amulets, I get caught up in determining goodness, as if that is the true measure of whether a life cycle moment should occur. Goodness, like naturalness, is the domain of the human men, who must protect their livers from demonic meddling, their wives’ dreams from infiltrating. Like the rabbis who curse Lilith for spilling their seed as they turn desirous in sleep, I want to know who’s to blame. Am I sick because of demons in my blood? Am I sick because, I settler, live in a paradigm in which my presence infiltrates indigenous homeland? I arrive not by crossing a welcoming threshold, but through force and genocidal policies, tangled up in human migration. How much am I part of the Empire at hand? Am I more demon or human? Is that a question of goodness or of whether I have agency to choose a variety of actions? For the rabbinic taxonomy that hinges on obligation is based on an understanding that demons and angels act on the world in one direction, unable to choose their one type of action. A demon is a tube towards the most material, separated realm of distinctions. An angel is a tube towards the most undifferentiated realm of oneness. In human-land, our realm in the middle, humans interact with a range of motions to the set and singular motions of angels and demons. Demons feed on and separate the body from itself, the home from its wholeness, a family from its status of complete security. They are drawn to life force in order to take that oneness and make it into distinct, consumable parts. If demons are as physically consequential as the ancient amulets suggest, should I keep trying to trap them? Will I actually be safer this way? If humans are somewhat like demons, as rabbinic taxonomies suggest, and since I’m not of the belief that we should trap and kill humans, or “demonize” humans carcerally, it’s hard for me to believe that demons are inherently evil or must be eradicated. To take a material stance, I must look to the larger web of life, and act in service of the continued hold of that web on the reality I live in. In other words, the webs of Empire and coercive control are just as tangled up in the material of this world as the living sky, the stones, the stories that we pass from generation to generation. And any action tugs at that web, reinforcing parts or straining others.

If settlers can be demons, infiltrating homes, then I can be a settler, burying this bowl. This version of reality would not be salient to the rabbis who mapped these taxonomies. The rabbis lived within Babylonian and Roman rule. When is taxonomy a danger to Empire? When a danger to the victims of State? When is taxonomy inherently violent and useful? Rather than taxonomic purity—What is the whole? Where does a cycle of self begin? What consciousness is activated? How porous?

They are hungry. Anything is possible. These bacteria could eat the whole world. They’ve been yearning. They act quickly, popping the bubblers, devouring what’s in their path. They eat each other, get too full, and die. They have been waiting for this.

The soil rests comfy. Within them a well-established fine web of mycelia, nettle roots, daffodil bulb, insects and worms. Polyphonic breathing—the exchange and rhythm. A sharp jag—somewhere along the pathways, a rupture. Sudden sting of acid on tender root tips. Flood of nitrous bile.

When a holy life becomes a death, ghosts reverberate from life. Ancient amulet users, so afraid of demons drinking domestic blood, of reverberations within the domestic sphere. Boomerang effects. A return to scientific empiricism, which is to say, Western eugenics. Are ghosts just whatever smudges on human thoughts or the actual life force of the demon? What do the ghosts want? Maybe demons don’t have ghosts–in life, they seek out life, and in death they seek out a way to fall apart, to give that life force back into decay, eventual rebirth, re-watering soil. Precipitation of ideology in which everything non-human is pure and simple. I don’t believe we are the only life forms that have muddy emotional relationships to ethics.

A small beetle senses a ripple when the body pops from the pressure, a subsequent soft deflation in the soil tension. They make their way over, routing around worms squirming through tunnels made by the reaching of roots, mycelium's grasp. Water tapping, trickling over ceramic, the hardened form buried in its own beginning, a slow maintenance of wet pressure, until this beetle, too, is damp. In the surrounding clay-heavy soil, they taste medicine, a wash of iron.

As the nettle roots over-feed on nitrogen, their skin blisters, shrivels, cell structure caving, the once-taut stalk collapses. They are disintegrating into their constituent parts.

Amidst demon-fall, a biome flourishes! A mite peers around at shiny. They covet the internal structure, want to make this a home. They are well-fed in this depth, but their belly aches for more. Will there be enough in time? They listen for the hiss of bigger bugs.

A long-nosed pincer smells the proteins in the egg yolk and burrows towards it, ready. They pierce the shell and the white goo beads up at the puncture. They suck it out with a long proboscis, tiny flakes of egg shell in their hairs, then scuttle away so as not to become someone else’s lunch. There’s a pressure here, above the egg. Something tangled and potent, but none of the bugs are going to fuck around with that. It’s not for them.

Demon bowl technology is designed to protect the human body, and is based on a science (a system of understanding the world) in which demons are real and dangerous.

According to scientist and educator Kendra Krueger, “a technology is anything that can store, transform or transport energy, matter, or information.” Incantation bowls utilize a combination of ancient technologies: Pottery—the transformation of matter through fire. Writing—the transportation of knowledge into the future. The bowls store demons, which I am agnostically considering energetic.

The ceramicists’ encounters in clay are preserved through extreme heat. The existence of each bowl implies a maker, a self with their own desires, however shaped by the social ecosystem around them. The artist Gabriel Orozco describes how the shape of his works in clay represents what just happened as he was thinking and moving. What was each bowl maker experiencing as they formed each bowl? Did they have a favorite tool for carving an inscription? A secret riverbank where they sourced their favorite clay? What information is encoded in the bowls that is illegible to an uninformed observer?

I’m in the ceramics studio, impatiently finishing my projects before I leave town, when a siren sound starts playing from the phones throughout the room. I overhear someone reading the city’s emergency alert aloud: a chemical spill in the Delaware River; buy bottled water, and don’t drink the tap. Speculation flecked with information ensues: a factory spilled latex, we’re fine in West Philly, we get our water from the Schuylkill.

I’m new to Philly, taking this ceramics class to make friends. After the stores are emptied of bottled water, I learn from an acquaintance that this same factory responsible for the latex spill has released many kinds of toxins into the Delaware River over the past two decades at least, but they reincorporated as a new company and the old records were expunged. The Delaware River, as I’m coming to know it, home to much aquatic life, a holy being in its own right, supplies drinking water to people in Lenapehoking, also known by the settler names of Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey.

I use some of my extra clay to make crumbly looking bowls, rough and uneven, unlike the smooth museum specimens. Two are the size of my fist, the third more fit for soup. They will shrink in the kiln. I make them as an experiment, to see what it feels like to try my hand at this art, knowing what I know now about the bowls' history. They are not big enough to trap the CEO of Trinseo, and much too large and porous to sieve the latex chemicals in the water.

The nettle roots are tentative at first and then hungry. Grasping, squeezing, sucking. Fertilized and sending their bounty up through stem. Prickers sharpen, more erect.

The human may be tempted to check on the progress of their demon trap. They may notice disgust at what is unfinished. The smell of falling apart. Impatience leading to acceptance. A bit of awe. If this is going to work, they need to wait. They may dread their own eventual disintegration, hope to avert that eventuality a bit longer by laying the bowl back down.

It is satisfying to squirm through the wet soil. A maggot brushing against the hard exoskeletons of shiny beetles, swarming. The give of an eye socket, blood sticky on the tongue and fruity, a little past its prime. A desirable flavor. Falling asleep to the clicking of mandibles. Muffled foot fall. What dreams befall maggots that nest in demon eyes?

To the later arrivals, papery demon wing residue tastes like dry yearning for the life force of insects buzzing in summer fields.

Secure in their place among the grains of sand, worm feces, and clay squeezing tight the water, a buried seed receives information about a shuffling beetle overhead, first brushed by shadow, then an absence signified by grainy light. Kinetic shivering, UV pinpricks. The seed-force begins to sense in a way they haven’t before, their wholeness splits. Slickly succumbing to the pull of the sun and the tug of the earth’s core. Spiraling forth from how they were, the heat and energy penetrate their pores. As they are grasped, they clutch the soil, unfurl sensors. They seek the rippling sensations of air, the wet, the yearning. They are met in their desires by a lush world. They develop branching rituals, find their root tips in material soft and potent, sink into this magic, the fibers on their stalk prickle, their leaf tips perk, an unknown in them bursts and feathers. They remember their seed-form, they want to bless. They learn restraint, constriction, system, and funnel. They siphon this found source. They purpose. They sequester, they blossom. They coax, they sigh, they pistil, they stamen, they produce, they go to seed.

Image credit for all images: Demon Bowl Lessons, 2024, Miriam Saperstein